Lost in suburbia

…is how I spent my first days in Tokyo, deeply intrigued by the rhythm of urban life that, as I have mentioned previously, felt surprisingly comfortable despite its newness. I was shocked by the atmosphere of well-inhabited organization; safe clean stillness.

As you can imagine, this atmosphere of organization somewhat clashes with the principles of graffiti, a style of expression that thrives in chaos, contestation, and questionable legality. I clearly remember stumbling upon a few scattered scribbles on handrails and park benches, hoping dearly that these were not the signatures of the famous Japanese street artists I had heard so much about. Where were the legendary sticker artists? Where was the uniquely Japanese graffiti style? Where was WANTO?!

Fortunately, I eventually made it to Shibuya, a neighborhood in Tokyo marked by the presence of youth culture. The artistic, rebellious, queer, niche subculture identity thrives in Shibuya, and naturally so does the street artists.

Bear with me while I go on a bit of a tangent. When attempting to understand street art style and graffiti culture, obviously one cannot gleam much insight or information from online research, but it can nonetheless provide useful points of reference. Before coming to Japan, I did some preliminary research; read some articles online, got deep into some subreddits, spoke to a few Singaporean artists who are linked into the “Asia graffiti scene”. One name kept popping up: WANTO.

It became my immediate mission to find WANTO. The WANTO style isn’t one that I particularly resonate with. It closely resembles the New York ‘wild style’ look, larger pieces are multi-colored bubble letters, while smaller tags are simply ‘WANTO’ spelled out in a variety of places. But regardless of the fact that it isn’t my cup of tea, I felt I had to pay my respects to one of the legends of Tokyo’s graffiti world.

So, as you can imagine, I was overjoyed when one day while walking through Ebisu, an area just South of Shibuya, I found it; WANTO scrolled across a highway overpass, accompanied by a few other big names, 10 FOOT and RESQ. This style of graffiti is called ‘Heaven’ and centers around placing tags in ridiculously difficult to reach locations, naturally demanding a certain amount of respect from other taggers.

This felt like a big victory. If I could find WANTO, I could find other famous artists, and hopefully discover some less-known artists that had nevertheless made their mark on this city. I was not disappointed. In the coming days, I stumbled across a few BIG names in the international graffiti scene.

Andre the Giant, who is known for sticker graf placed excessively high on city poles. I’ve seen Andre stickers in cities around the world from Ho Chi Minh, to Barcelona, to Paris.

Ella & Pitr, who are known for massive murals that take up entire roofs of buildings. Ella & Pitr are legends in Mostar, the town I was living in in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Actually, they are two of the street artist that first inspired me to start tagging.

I’ve heard that both Invader and Banksy have also made their marks on Tokyo, two artists that are somewhat cliché in my opinion, but regardless I am hoping to find their pieces in the coming days.

All of these discoveries are interesting, and certainly provide some insight into the street art scene here in Tokyo, but I think they fall short of really revealing a uniquely Tokyo style. WANTO is obviously famous, but I see little in their work that is especially different from graffiti in many other places. Andre the Giant, Ella & Pitr, Invader, are all legendary artists, known around the world for their work, but they do not originate from Tokyo, and thus cannot serve as a particularly useful window into Tokyo graffiti culture.

I didn’t come here to explore graffiti in general, I came here to delve into specifically Tokyo’s graffiti, hoping that I could use this form of expression to better understand how urban intentional communities arise and are maintained. Zul Othman (ZERO), a Singaporean graffiti artists and an important role model for me and many others, once told me that exploring the graffiti of a city is one of the best ways to understand the counter culture of that place. Is the style rebellious, reactionary, or comical? Are the messages political, personal, territorial? Are tags hidden under bridges, or throw openly onto billboards?

If you asked me to some up the Tokyo graffiti style in two words, I would say: humorous and absurd. Especially the sticker graffiti takes a completely nonsensical form, cartoonish distorted faces plaster lamp posts and electrical boxes across the city. They seem to exists simply to confuse and entertain. Each absurd splat of creativity seems to be forcing the viewer to question the straightforwardness of reality. They imbue the urban spaces they occupy with a fantastical playfulness that I have rarely seen from graffiti. While most tagging asserts dominance, claims territory, owns space, these absurdities laugh in the face of competition.

Interestingly enough, I have found many parallels between this absurd sticker graffiti and the absurdist Japanese literature I have been readings since I arrived. I started with The Last Children of Tokyo by Yoko Tawada, a beautifully written dystopian environmental novel. Tawada writes with an incredibly nonchalant surreal style that questions the very fabric of our current world. This text is deeply political in nature, and yet it avoids being moralistic. She intertwines completely non-linear similes into the entirety of the novel in a way that feels deeply similar to the absurdism of this graffiti. I am currently working my way through Haruki Murakami’s Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, which contains a similar absurdism.

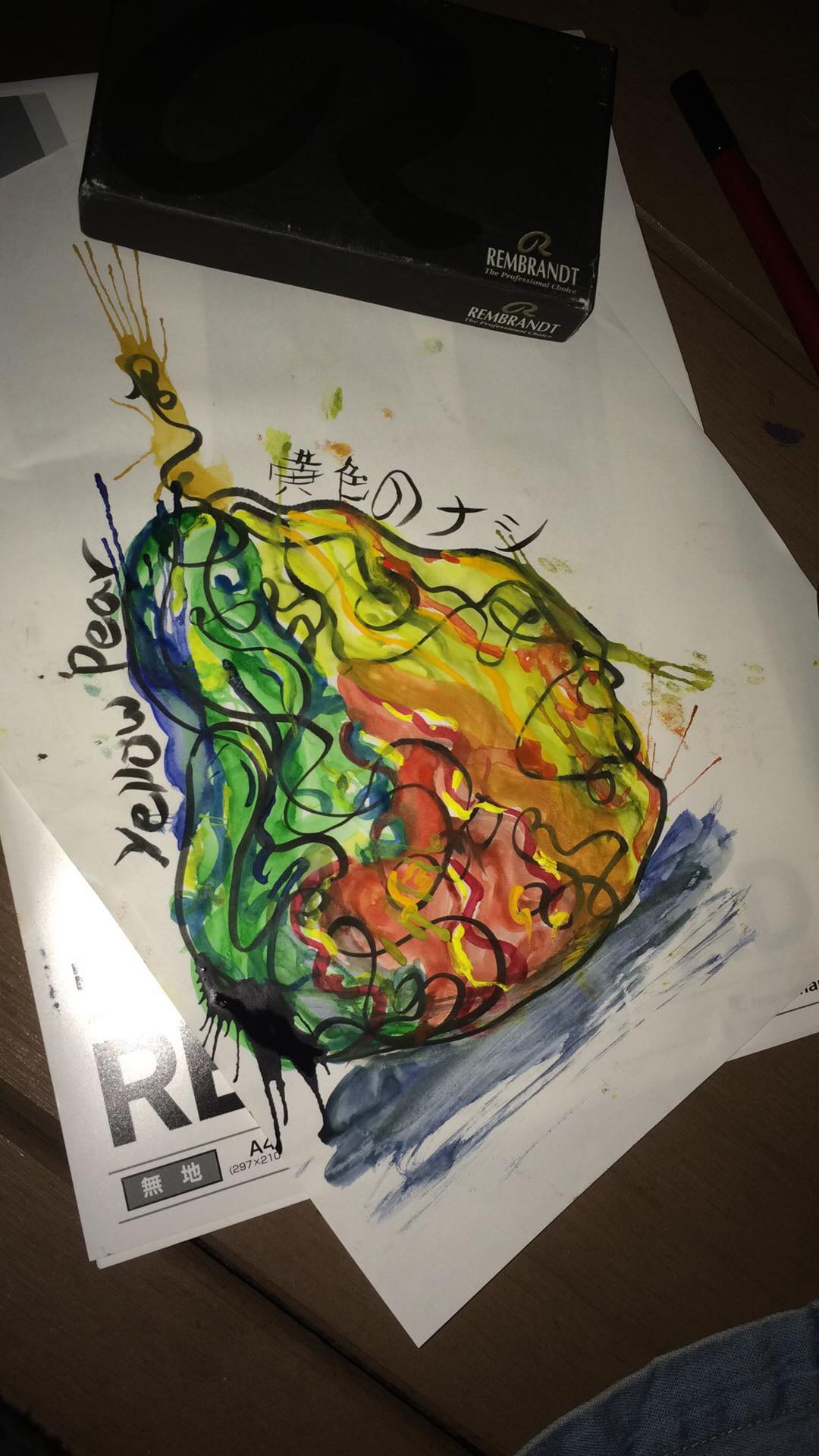

Inspired and motivated by this absurdist art, I have begun creating my own set of water colors and sketches that react and imitate the style I have observed. These are the beginnings of my newest tag: Yellow Pear.

I want to end with a request for the reader. Please take all of these reflections not as an objective or absolute analysis of Tokyo culture, but simply as my interpretation of, and reaction to, the art I have stumbled upon. These reflections are in many ways an imposition of thought and experience onto a space, and in the process of imposing thought one must constantly be wary of exoticising.

Thank you for reading. Here is a picture of sunrise from the banks of the Naka River.

Loved reading this post, Boden 🙂

I have never read or explored the graffiti scene—Didn’t even know that tagging was a thing, or that artists all over the world go everywhere to tag different places with their stickers or artwork. I find that incredibly interesting and cool!

Was just wondering, though, even though a lot of the artwork you have seen are international graffiti artists, does that mean it is not ‘Tokyo style’? What does ‘Tokyo style’ mean and could you be trying to find something to fit a pre-concieved idea of what you think is local ‘Tokyo style’?

Love the pear.