MANILA

Anmei

The first memory I have of Manila is stepping eagerly out of the airport, only to be immediately wacked with an abrupt curtain of sweeping, hungry rain. It’s not that I’m unaccustomed to tropical thunderstorms–after a year living in Singapore, I am all too familiar with them. It’s just that it wasn’t the greeting I expected from the Philippines. Later, our local friend would explain to us that monsoon season had hit Manila at exactly the same time that we had landed in Manila. So that was great timing.

The first thing I noticed about Manila was that the people there are generally so nice. Or very polite and respectful, at the very least. If you approach a local on the streets of Manila, 8 times out of 10 they will be able to respond to you in English, and 9.99 times out of 10 they will address you as “sir” or “ma’am” and pleasantly sit through all of your questions about directions or menu items or why the traffic in Manila is so awful. That was surprising to me, and the warm and accepting nature of the Philippines is something I inquired about to locals later on. Looking back, it’s kind of ridiculous. It’s who they are; it’s not their problem that I’m used to colder, less friendly cultures. At any rate, I became very grateful for (and slightly in awe of) the social atmosphere in Manila after our 10 days there.

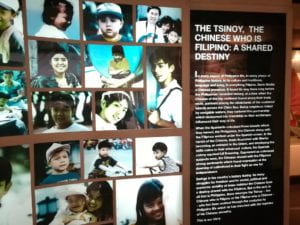

Perhaps the accepting nature of the Filipino culture is a reason why, when we asked our interviewees about discrimination against the ethnically Chinese in Manila, they responded that they had never really faced any. At first, that was strange to me–a minority ethnicity (albeit the largest minority ethnicity in Manila) escaping discrimination–because of my upbringing in a country where all minority ethnicities experienced some degree of inferiority. When Nicole and I probed deeper, we discovered that there was a darker side to the “accepting” nature of Filipino culture. Our interviewees attributed this quality of Filipino culture to all the colonization endured by the country throughout history. The Philippines was colonized by the Spanish, Americans, and Japanese. Some of the Chinese-Filipinos we spoke to explained that, until recent history, the Philippines has always been in some type of “patron-beneficiary” relationship: the colonizer was the “boss”, and the Filipino people felt that it was up to them to serve the boss. While the Philippines is no longer under colonial rule, this patron-beneficiary culture has remained and Filipinos still look towards a “boss”–which is now the ethnically Chinese, to some degree, because the Chinese have relatively high economic standing in the Philippines and own many of the largest businesses. So this is an explanation for why there isn’t much negative discrimination against the Chinese-Filipinos in Manila and maybe also for why Filipinos are so gracious and accepting. As one of our local friends put it, Filipinos suffer from an “inferiority complex” as a consequence of years and years of colonial rule, so they view themselves as inferior and are incredibly respectful and kind to everyone else

I want to take a moment here to recognize that these are some of the opinions of the people in Manila we spoke to, who come from a selective social pool. What I’ve written are certainly generalizations and contain bias. But what I wrote is significant to me because learning about this phenomenon from locals led me to realize that the polite, complacent, and accepting culture I was first very impressed may have derived from a dark and ugly cycle of oppression. In some ways, it was a wake-up call. Maybe if I hadn’t been on this research project and remained in Manila for longer than a week to have real conversations with locals–if I had merely been on vacation–I wouldn’t have reached any deeper understandings about Manila at all. In this way, the Travel Fellowship has effectively taught me to pause, look at and listen to what is really going around me, and always be mindful of the fact that– while first impressions are important–my first impression of a culture may be far from representative of the culture’s true history or deeper influences.

Manila showed me something beyond our research proposal question: that it is useful to think about the action of traveling itself. Now, I recognize that the way in which I travel determines the type of cultural knowledge I gain. It’s not necessarily that being a tourist is bad. Sometimes, being a tourist is unavoidable. But I think that the next time I am on vacation, as a tourist, I should be mindful of the potential pitfalls of grazing a culture and the rewards of slowing down to probe. After all, what I learn about a culture in a country I visit is what I will end up sharing to my friends, family, teachers, strangers I meet, etc.–and to me, that’s hugely important because if I possess an inaccurate or largely biased impression of a culture, that will spread. So I hope that I, and other travelers, will travel mindfully to be able to share in a way that gives the cultures we encounter some justice (and whatever that may mean).