In Krasnoyarsk and Ulan-Ude, we talked to older people who grew up in the Soviet Union and witnessed its fall. As an American and a Singaporean, the stories we were told about the USSR tended to be negative, but we wanted to listen to stories from Soviet times with open minds. We didn’t make an audio recording of exactly what Victor and Protas said, so all of this is my retelling. I’m telling you a story.

Part 1: Krasnoyarsk—Climbing and the Revolution

Stefan and Victor.

Victor is probably in his fifties or sixties, but he seemed ageless. His skin was darkened by the sun due to all the time he’s spent outside since he retired, and his face was crinkled with laugh lines. Before he retired, he managed a plane and helicopter manufacturing plant here in Krasnoyarsk, where he’s lived all his life.

Melody at the base of the main rocks at Stolbi.

When Melody and I approached the main rocks at Stolbi National Park, we thought there would be a short two to three meter climb before we reached a path leading to the peak. But when we heaved ourselves over the first rock, only two meters off the ground, we found there was more climbing to do. An older man easily scaled the rocks in front of us and then beckoned us forward. Victor. Given his deep tan and the surety with which he climbed, we figured following him would be our safest bet. Without us noticing, Victor’s son Stefan fell in behind us.

About fifteen minutes in and ten more meters up, Melody and I realized we were far out out of depths. I’ve never been rock climbing before, much less without equipment. But without introducing himself, Victor continued to point out where we should place our hands and feet to climb. Fifty meters up, I looked down, and quickly regretted it. At that point, if I let go I would soar through the air…and then break on the rocks. The world narrowed to the slender footholds above me as I watched Melody carefully pick her way up.

When we reached seventy meters, we had to shimmy up between two rocks, but I couldn’t find the foothold. But Melody had survived it ahead of me. I could do it. I pulled myself up, gripping at the edge of the rock. My foot slipped. In the way time slows before a car accident, I vaguely regretted I hadn’t been strong enough to make the climb. But then Stefan’s hand stopped my sliding foot, and I used his palm as an extra foothold, clawing my way to the top.

“Dangerous!” said Victor. It was the first word he said to me. I nodded weakly.

Finally, Melody and I reached the top of the peak, tired and petrified after a 30-45 minute climb. The Siberian mountains were stunning—green and smoky blue, stretching around us in three directions. Now that we were no longer focused on surviving, we introduced ourselves to our nameless saviours and offered them almonds. While snacking, Victor shared that sometimes he would come here before work, running the 6km from the park entrance, climbing the rocks, and then running back. Now that he’s retired, he enjoys travelling outside the country to climb; he’s been to Nepal and Mongolia recently. Stefan works in Moscow now, and Victor teased him about growing weak since leaving Siberia.

At the top of the peak!

Let’s descend without dying!

After half an hour at the top we descended together, and once we reached the bottom, Victor told us he was going to go and see the other main rocks in the park—the Feathers, the Grandfather, and the Grandmother. “It’s much easier than this,” he reassured us. With my instinctive distrust of strangers, I was briefly unsure. But they had literally saved our lives, so Melody said we’d join them.

“We forgot that easy for them is not easy for us,” I said to Melody in Chinese as we labored up a hill a few minutes later. Privately, I wondered if we had an hour-long hike ahead of us.

“Stefan isn’t an expert,” she replied in Mandarin. “We can keep up with him.” It’s an indication of Victor’s fitness that Melody and I felt more confident in keeping pace with a 27 year old man versus his father.

We climbed the Grandfather first, where Victor shared more about his retirement and experimentation with shamanism and spirituality. First he started researching Freudian psychology and psychology of the body, and became interested in body awareness and consciousness. Then he discovered shamanism, and now wears a pouch on his chest to protect his spirit from the negative energy around him. Soon he’ll go to the Altai Mountains in Mongolia to act as a spiritual guide for tourists. Stefan remained quiet for most of this, and I thought how interesting the contrast between the two of them was: Stefan, working in Moscow, wearing name-brand exercise clothes; Victor stripped to the waist and fascinated by shamanism. But there was clearly deep affection between them, despite their differences.

We moved on to the Feathers, four slabs of vertical rock. I couldn’t believe anyone could climb them, so I asked Victor how it was possible.

“In Soviet Union days, we couldn’t go abroad for fun,” explained Victor. “So we came up here and climbed.” He pointed to the right side of the Feathers. “Fastest time up is two minutes,” he said.

“Using equipment?” I asked.

“No!” laughed Victor. Okay then. “Many famous alpinists are from Krasnoyarsk,” he continued. “On the way down, you slide down on your elbows. But you have to wear special sleeves, or else you will skin your elbows!” He laughed. “You go fast, very fast. And I know a man who can flip on the way down, from elbows to knees.” I looked back up at the Feathers in horror. That sounded insane. But I guessed with no other forms of entertainment, it made total sense to spend time climbing. In my mind, the clearing was suddenly full of young men and women, competing and climbing and risking their lives on dares.

“Have you climbed the Feathers?” asked Melody.

“Oh yes, yes!” said Victor. He stretched out his elbows like chicken wings. “I slid down!” Then his attention was caught by a plaque at the base of the Feathers.

“That sign!” said Victor. “There was a man who climbed and brought a photographer. But when you go up, it gets really wide, and you have to stretch—“ He held up one arm and the opposite leg. “You must stretch across with one hand and one foot. He slipped and fell, and the photographer got pictures.”

“That’s…horrible,” said Melody, stunned.

“Every year, one or two people die here,” shrugged Victor. “But there is only a sign for one man. Because there were photos.” On that cheerful note, we turned down a forest path, and I assumed we were descending the mountain. Purple wildflowers bloomed on either side of us, and I marvelled at the growth of only two months. Winter ends in April in Siberia.

We stopped at a rocky overhang with a plaque in Russian. All I could read was the years 1905-1906. “This is from the revolution,” said Victor. “Revolutionaries came here to plan, away from the police. This used to be a house, with a wooden front.” I stepped underneath the rock, and noticed the soot-blackened ceiling—a definite sign of former habitation. It was logical that revolutionaries met here, deep in the woods and far from the Czar’s police. The vastness of Russia hit me. In the days before CCTV and geo-location, how could you ever find anyone? Someone could just slip into the woods after dark, and no one would know…it was a terrifying and yet somewhat nostalgic thought. In the places I live, that kind of anonymity is long gone.

“Nearby is a place we call Dasha’s road,” said Victor. “Once there was a revolutionary, a Communist revolutionary named Dasha. She was a woman. And one day she was running from the police—the Czar’s police—and took this road that had a step—“ He gestured with his hands to indicate a small ledge“—and then a cliff. So the police were running after her and she jumped off the road down onto the small step. And the police went—“ He indicated soaring off the edge with his hands.“So now we call this Dasha’s road.”

As we proceeded down the mountain—not down Dasha’s road—I thought about the stories Victor told about the revolutionaries. That early, in 1905, people wouldn’t have known how the Bolshevik Revolution would go. They didn’t know about Stalin or how he’d insert himself in Communist ideology. All they knew was that the Czar and his family danced and drank while their children starved. I found myself admiring the revolutionaries for the audacity to imagine a very different world, a world of equality, without tyrants and warlords. I wouldn’t have had the courage.

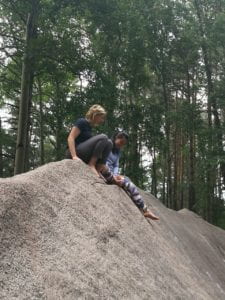

Melody and I climbing on some rocks, inspired by the stories of Soviet rock climbers.

We reached the park entrance, and Victor and Stefan waved us goodbye. Thunder rumbled ominously, and Melody and I prepared for a 6km slog in the rain. But it only sprinkled, and about an hour or so later we emerged back onto the road near the bus stop.

At the exit, hidden in the trees and half-covered by foliage was a Soviet-style statue of a man and a woman. It stood about four meters tall. There was no sign to explain its meaning, but I guessed it commemorated the revolutionaries who met in Stolbi forest over a hundred years ago. The statue seemed neglected and a bit sad. I wondered what Dasha would have thought of the past hundred years of history.

“Come on!” said Melody. We ran to catch the bus, leaving the echoes of the rebels behind.

As a child, my favourite picture book was Rumplestiltskin because of one illustration of a palace servant searching for the titular character. The picture took up two full glossy pages, and depicted a dark and mysterious forest. The servant woman wound her way through the trees, head covered with a handkerchief and lantern aloft. Only the light of her small flame illuminated the woods around her as she wandered near and far. And in a corner was a small bonfire, around which danced a wicked and magical creature…

Found this illustration from the same book.

Thanks to Victor’s stories, the otherwise ordinary forest outside Krasnoyarsk will forever be full of revolutionaries, their lanterns the only specks of light in the deep woods. It’s too late, but I wish them luck.